1 - ESP-IDF getting started

Programming native applications on the Badge requires an ESP

IDF to

be installed. IDF stands for “IoT Development Framework” and is Expressif’s

SDK which provides:

- convenient access to hardware functionality

- implementation of protocols such as TLS, HTTP and MQTT which are

commonly used in IoT projects

- common utilities such as logging, error handling and JSON parsing

- infrastructure code for building, flashing and debugging.

The IDF will be installed automatically (via git submodules and make commands which we

will point out) but it does require some dependencies to be installed.

Installing Prerequisites

How to install these prerequisites is described on the IDF documenttion page for:

The instructions will (mainly) install git, cmake and python. Remember you DO

NOT have to install the IDF!

In order to sideload the apps you develop, you will be using our webusb

tools. These tools will get

automatically installed, but require pyusb to be installed. This can be

installed with pip install pyusb or apt install python3-usb

Download & build the “template app”

We created a basic Hello World template

app that’s intended to be

used as a basis for native badge apps you build. To allow you to get started quickly, the

template app downloads the IDF in the required version, as well as some badge

specific components you will.

To clone the template app, open a shell:

$ git clone https://github.com/badgeteam/mch2022-template-app my_fancy_app_name

$ cd my_fancy_app_name

The

Makefile

in the template app contains a number of targets for your convenience:

prepare : Download all the ESP32 dependencies needed to build, you only need to run this once!build : compile the codeinstall : install the app you just compiled (NOTE: if you have previously

used the IDF to build ESP32 code, this is different from regular flashing! see below)monitor : connect to the ESP32 console and look at your log files.

$ make prepare # this downloads all the dependecies and may take a couple of minutes

$ make build # this compile your app

$ make install # this installs the successfully compiled app to a connected badge.

# you really only need '$make install' because it depends on `install`.

It will take a couple of minutes to download all the components. Once completed, a simple app

showing “Hello, World!” will run on your badge.

Difference to “normal” IDF

If you have previously used the IDF, you may have noticed that we don’t use idf.py flash to

install the app on the Badge. (And if you haven’t, you can safely skip this section. :)

The idf.py flash command assumes that the binary to flash is the main

application for the device. This is not the case for the Badge, though. The

main application is the

launcher app, i.e. the

app with the menu that starts by default. The make install target of the

Makefile copies our newly created app into the

appfs

instead of overwrting the launch. Once copied to the appfs, the launcher can

find it and the app should appear in the apps menu.

Obviously you can use idf.py flash but you’ll delete the launcher

app and would need to reinstall it later.

Customizing the template app

Finally! Now that we have all the bureaucracy taken care of, we’ll start off by

modifying the message printed to the screen. Have a look at this

line

of main.c, you can see the text shown on screen:

//...

// This text is shown on screen.

char *text = "Hello, World!";

//...

This part is responsible for drawing the text to the screen.

Go ahead and try to edit the text, here shown as “Fancy App!”:

The buttons on the Badge are not directly connected to the ESP32, instead they

are read by the rp2040 coprocessor via I2C. Have a look in the

esp32-component-mch2022-rp2040

component in case you are interested in the details.

The button handler starting on this

line

of main.c currently causes the app to exit and return to the launcher

whenever the HOME button is pressed.:

//...

// Await any button press and do another cycle.

// Structure used to receive data.

rp2040_input_message_t message;

// Await forever (because of portMAX_DELAY), a button press.

xQueueReceive(buttonQueue, &message, portMAX_DELAY);

// Is the home button currently pressed?

if (message.input == RP2040_INPUT_BUTTON_HOME && message.state) {

// If home is pressed, exit to launcher.

exit_to_launcher();

}

// Is the home button currently pressed?

if (message.input == RP2040_INPUT_BUTTON_HOME && message.state) {

// If home is pressed, exit to launcher.

exit_to_launcher();

}

//...

Let’s change this behaviour so the screen is briefly pink after pressing the A button.

Graphics for the badge are handled by a library called Pax, if you want to dig deeper

have a look at the docs here

Pax uses the same RGB (well, ARGB, to be precise) hex triplets as HTML.

0xeb34cf is beautiful MCH pink.

//...

// Button handling.

if (message.input == RP2040_INPUT_BUTTON_ACCEPT && message.state) {

// Make a pink background.

pax_background(&buf, 0xeb34cf);

// Update the screen.

disp_flush();

// Wait for half a second.

vTaskDelay(pdMS_TO_TICKS(500));

// After this, it loops again with a new random background color.

} else if (message.input == RP2040_INPUT_BUTTON_HOME && message.state) {

// If home is pressed, exit to launcher.

exit_to_launcher();

}

//...

Using WiFi

The template app you’ve been playing with has a simple WiFi connection

API.

First, empty the while loop so it looks like this:

//...

while (1) {

// Await any button press and do another cycle.

// Structure used to receive data.

rp2040_input_message_t message;

// Await forever (because of portMAX_DELAY), a button press.

xQueueReceive(buttonQueue, &message, portMAX_DELAY);

// Is the home button currently pressed?

if (message.input == RP2040_INPUT_BUTTON_HOME && message.state) {

// If home is pressed, exit to launcher.

exit_to_launcher();

}

}

//...

Instead of writing “Hello World” to the screen, we will modify the code to

change the background color to indicate our Wifi connection status. Call

wifi_connect_to_stored() to connect to WiFi and set the background color

depending on whether the function returned successfully.

//...

// Init (but not connect to) WiFi.

wifi_init();

// Now, connect to WiFi using the stored settings.

bool success = wifi_connect_to_stored();

if (success) {

// Green color if connected successfully.

pax_background(&buf, 0xff00ff00);

} else {

// Red color if not connected.

pax_background(&buf, 0xffff0000);

}

disp_flush();

//...

What you want to do with WiFi varies a lot, so we can’t explain that here. But

if you have other libraries that need WiFi (for example an MQTT client), you

start them after this code.

Sharing is caring!

Now you’re ready to publish your app in the Hatchery. Follow these instructions to publish your app.

For further information:

2 - A More Advanced Example

If you have reached this page, you have probably already had a look at the

template app and played

through the getting started tutorial. If not, it

might be a good idea to do it now - there’s a lot of information on getting the

prerequisites installed.

You will need a computer with libusb, pyusb, git, cmake, make, python3, a

terminal, a web browser and a text editor. This should be easily doable on

Linux machines and Macs - if you’re on Windows, it’s probably easiest to work

in a Linux wrapper but YMMV. Additionally, a github account is helpful but not

strictly needed. Check here for details.

This journey assumes that you have some basic familiarity with shell, C and git

(or a search engine of your choice). This is not a line-by-line tutorial, it

just gives you the rough outline of writing an app and discusses some

approaches and techniques along the way. If you want to cheat and download the

finished project, go here

Starting

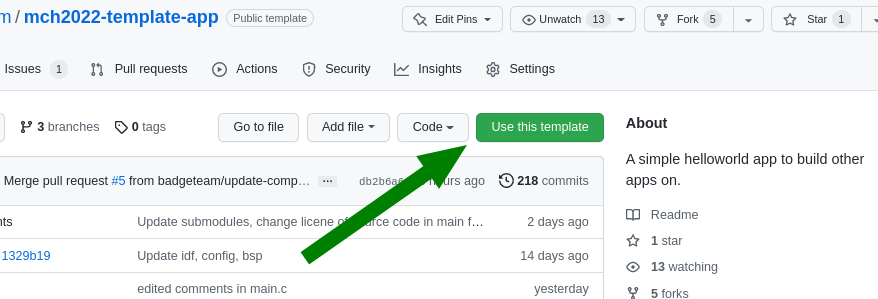

Start by cloning the template

app - go there, click on

“Use this template” and follow the instructions to make your own copy (or you

can clone the repo and add a new remote manually). git clone the repo,

cd to it and run make prepare. This should set up the ESP-IDF and

all badge-specific components.

What should we do?

If you’re not sure what you want to hack, the ESP-IDF examples are an

amazing starting point. They are already on your machine: ls esp-idf/examples.

Hours of happy browsing. Besides covering many features of the ESP32, they are

exceptionally well written and documented (usually).

We’ll use one of these app to build our app - something that can’t be done in

the BadgePython world: Let’s turn the Badge into a bluetooth Boom Box. Speaker

sound quality will most likely be worse than any smartphone on this planet,

but with the headphone output, this thing might even be usable for something.

There’s a working example at

esp-idf/examples/bluetooth/bluedroid/classic_bt/a2dp_sink.

The code example already shows how to hook the audio stream to an I2S

(Inter-IC

Sound)

DAC. And conveniently, the Badge’s audio outputs are connected to an I2S DAC!

Almost like we’re done already before we even started.

Shameless Copying

To get started, copy the following files from the IDF project’s main directory:

bt_app_av.h, bt_app_av.c, bt_app_core.h, bt_app_core.c into your own

main folder (they are Public Domain, after all!). And while you’re at it,

copy most of the contents of the main.c file over to the end of your main.c

file and the includes to the top.

Actually Hacking Some Code …

Start by integrating the bluetooth initialization routine into your app. Rename

the bluetooth example’s app_main to bt_init and call it within our

app_mainfunction in place of the call to wifi_init ( we won’t be

using WIFI in this example). bt_init must be declarated above app_main

code. Either move the whole function up, or add a declaration.

Unfortunately, both app_main and bt_init call nvs_flash_init.

And nvs_flash_init may only be called once. Get rid of the second

call.

The example projects defines a number of constants using menuconfig. These

are defined in

Kconfig.projbuild,

but we don’t need them. For example, this mechanism in the original IDF example

allows you to redefine the I2S pins to use, but these are hardwired on the

Badge, so configuring them adds unnecessary complexity. grep through main.c

looking for CONFIG_EXAMPLE and replace them:

CONFIG_EXAMPLE_A2DP_SINK_OUTPUT_INTERNAL_DAC : should be false, this option would route the audio to the ESP’s internal DAC, but the Badge has a dedicated audio DAC chipCONFIG_EXAMPLE_I2S_BCK_PINCONFIG_EXAMPLE_I2S_LRCK_PINCONFIG_EXAMPLE_I2S_DATA_PIN

We need to find the new values for the I2S pins

CONFIG_EXAMPLE_I2S_BCK_PIN, CONFIG_EXAMPLE_I2S_LRCK_PIN and

CONFIG_EXAMPLE_I2S_DATA_PIN in i2s_pin_config_t. Obviously, you can

find the pins in the hardware

schematics,

but there’s an easier way: Have a look at

components/mch2022-bsp/include/mch2022_badge.h.

The Badge’s board support package has defines for all pins. (Note: At time of

writing, this header had LRCLK and BCLK swapped, but hopefully this will be

sorted out soon).

The components directory is generally a good place to look if you’re

looking for Badge drivers. All items in this folder are independent components.

You can imagine them as libraries. They are automatically added to the project

by the ESP-IDF build system.

I2S has some sloppy signal naming rules, which may be confusing. LR is LRCLK (a

word clock), CLK is BCK (a bit clock) and DATA is DATA. In addition, our DAC

wants a MCLK (usually faster than the bit clock), so we add an entry:

.mck_io_num = GPIO_I2S_MCLK. In the end, it should look something like

this:

i2s_pin_config_t pin_config = {

.mck_io_num = GPIO_I2S_MCLK,

.bck_io_num = 4, // should be GPIO_I2S_CLK

.ws_io_num = 12, // should be GPIO_I2S_LR

.data_out_num = GPIO_I2S_DATA,

.data_in_num = -1 // not used

};

i2s_set_pin(0, &pin_config);

While you’re at it, you can tweak the I2S parameters to our needs (located directly

above the pin_config code). I2S has half a dozen different dialects and

each I2C peripheral speaks a different one. Getting the parameters right is not

hard but tedious, requiring comparison of

datasheets. Additionally, because

the I2S peripheral will stream audio data via DMA, we can adjust buffer

sizes. Here’s some settings that seem to work well:

i2s_config_t i2s_config = {

.mode = I2S_MODE_MASTER | I2S_MODE_TX, // TX only

.sample_rate = 44100,

.bits_per_sample = I2S_BITS_PER_SAMPLE_16BIT,

.channel_format = I2S_CHANNEL_FMT_RIGHT_LEFT, // stereo

.communication_format = I2S_COMM_FORMAT_STAND_I2S,

.dma_buf_count = 6,

.dma_buf_len = 128,

.intr_alloc_flags = 0, // default interrupt priority

.bits_per_chan = I2S_BITS_PER_SAMPLE_16BIT,

.tx_desc_auto_clear = true // auto clear tx descriptor on underflow

};

i2s_driver_install(0, &i2s_config, 0, NULL);

Almost Ready to Try

We’re close to getting something working. Just four things before we try our first build:

- Change our app name: The projects Makefile contains an

install target.

It’s purpose is to push the project’s binary to the Badge during development.

The name in quotes is the name shown on the Badge’s app chooser. Change it

something unique. - Change the Speaker’s name: There’s a

#define that we copied over from

the bluetooth example: LOCAL_DEVICE_NAME. This is the name broadcast

via bluetooth. Change it to something unique. idf.py menuconfig: menuconfig allows you to enable and configure the

components in your project. First, enable bluetooth. Start the tool with

make menuconfig, go to Component config > Bluetooth and enable it.

Go to Bluedroid Options and enable Classic Bluetooth and

A2DP(Advanced Audio Distribution Profile = what bluetooth speakers do).

Later on, menuconfig is a good place to disable unneeded software

components. For now, we don’t care.- Add files to compile: Remember that we added additional ‘*.c’ files,

bt_app_av.c and bt_app_core.c? The project’s build process works

roughly as follows: make build triggers idf.py build which in

turn uses cmake. For now you don’t need to understand this in

detail,you just have to tell the build system about the new files. We need to

edit main/CMakeLists.txt. When you’re done, the SRCS section

should look something like this:

SRCS

"main.c"

"bt_app_core.c"

"bt_app_av.c"

Now it’s time to make. Type make prepare, this downloads all the

prerequisite tools and code. This process might take a while. It will fell like

an eternity. Meanwhile, whistle the Jeopary theme song. Drink some water. Wash

your hands. Give a polite, honest compliment to a stranger.

The make process should have finished by now. Now type make build. If this

fails, you probably didn’t follow the steps properly (most likely the

compliment part). No worries, subsequent builds will be faster.

Now, run make install. If there’s an error concerning missing USB, repeat the

libusb and pyusb install steps. If you get a

UnicodeEncodeError in printProgressBar, you’re using a Mac and you

can solve this problem by editing tools/webusb.py: Replace the fill

character with another character, e.g. *. Or fix it and create your first PR

to the tools repo!

If everything went as expected, you should see a WebUSB screen on the Badge and

a progress bar in the terminal. Once upload and verification completes, the

Badge should reboot and show the “Hello world” screen of the template app.

… Boring!

Take your phone or other bluetooth device, scan for new devices. Select

BadgeBoomBox or whatever you chose for your speaker’s name and pair them.

Make sure the speaker switch on your Badge is turned on. Play some music. Hear

it? That amazing sound of no bass? Unbelievable.

Understand What’s Going On

Good work! Let’s take a short break and look at what the app is doing (hey,

we didn’t write much of it yet). ESP-IDF has a logging

facility

that is used in the example code (look for ESP_LOGI, ESP_LOGE,

ESP_LOGD etc.). We can monitor the logs with make monitor (if it

does not work, you might want to set the PORT environment variable to the ESP’s

/dev/tty* ). If you succeed, you will see bluetooth connection and

disconnection events and all sorts of interesting things happening. For

example:

There are “volume change simulation” events. Too bad we didn’t look into the

example before - the example code simulates volume controls and a user

randomly turning the volume up and down to showcase the AVRC (Audio/Video

Remote Control) features. This has to go. But just the “random volume change”

part - we may want to hook the volume control to our

buttons. The simulation is executed in a separate task, look for

s_vcs_task_hdl in bt_app_av.c and surgically remove it from the

source code along with volume_change_simulation.

If you connected specific devices, e.g. an Android phone, you might be

surprised to see that the phone will not only send connect/disconnect and

play/pause events, but sometimes also track titles as well as album and

artist names. Wouldn’t it be great to see this on the screen?

AVRC is not consistently used by all devices. Some features are used, some not.

Anyway, let’s have some fun with it.

Another nice thing to have would be a dB-Meter. Our next task is to sift through

the code to see where the audio stream passes by to analyze it.

Side note: Tasks, Events, FreeRTOS messaging and our threading approach

ESP-IDF makes heavy use of FreeRTOS. Two essential building blocks of FreeRTOS

are Tasks and Queues. Tasks can be seen as threads: Independent,

preemptively scheduled sequences of operation. Each application has a main

thread (the one that executes app_main), a timer thread and possibly other

threads (e.g. for bluetooth, Networking and other things). Queues are often

used to pass events and other information from one task to another. They are

basically thread-safe FIFO buffers. One task (or an interrupt) posts elements

into the queue and another task can wait for elements to arrive in that queue.

The template app already uses one queue: The RP2040 firmware will post

button presses into this queue. The application’s main loop waits for button press

events to arrive and reacts to it by setting a new random color and redrawing

the screen.

The bluetooth stack uses its own tasks. Our task, the main task, controls the

screen and user interaction (and it’s a good idea to restrict this to a single

task). So if we want to receive bluetooth information in the main task, it’s a

good idea to use a queue. bluetooth event -> queue -> main task

reacts.

But our main task is already blocked waiting for the button press queue! How

can we receive our Bluethooth events? Could we use the button queue for our

bluetooth events? Yes you could! But it’s not polite to push things into

other’s queues without prior consent. So we don’t.

There’s another option: Queue sets are used to combine queues and

(other things) and wait on several events simultaneously.

So we’ll create a new audioQueue to send us messages whenever there’s

a relevant bluetooth and/or audio event. We also use this queue to send

audio level updates regularly.

Queue entries can have data attached to them. This is often a struct with an

event type and additional data, typically implemented as a union so that

different events can have different data associated with them. It’s good

practice to keep these entries short because queues will have to allocate

several instances prior to usage (Real Time OSes prefer allocating a fixed

amount of memory at start instead of dynamically allocating memory during

runtime).

To keep the queued data short, we will not include the full audio stack state

in the queue entries. Instead we’ll generate an event to notify that the state changed, but

not what actually changed. For this, we use another mechanism to get data

safely from one task to another: Semaphores used as mutexes / locks. The

bluetooth stack will collect its own state in a struct. The main task can

request a copy of that state struct. All accesses to members of that struct

will be embedded in a lock, making sure that only one task has access to this

struct at any instance in time.

Queues are good for pushing information from one task to another, mutexes are

good for pulling. Admittedly, we could have used just queues in this case, but

this example is supposed to be at least slightly educational…

In addition to the “something changed in the bluetooth audio state” event, we

will have a dB-Meter-update event that should be sent in roughly 20-50Hz

intervals so that we can have a smooth noise meter animation.

Who should manage the queue? The queue could be located either in the

bt_app_*** part or in our main.c. Both are good options. We will

add them to main.c, reasoning that the bt_app_*** is a generic service

and should not make any assumptions about hosting application. As a

consequence, the bt_app_*** part will just issue callbacks whenever

something interesting happens. The code we’ll write in main.c takes care

of queueing these events.

We will leave the well-paved path of documenting every changed part in the code

here. The remaining document will show some examples. As said, the full code is

in the repository.

After some light reading, you’ll quickly get a better overview over the

bluetooth app: naming suggest that bt_app_core.c seems to do the actual

streaming while bt_app_av.c handles metadata and remote control. So the

audio data is more likely to be found in bt_app_core.c. And metadata is

most likely found in bt_app_av.c.

We need to decide: What data is useful for us? What could

we want to display?

- Connection state: Whether we’re disconnected, connected, connecting or

disconnecting

- Audio playback state: Whether we’re playing, stopped or suspended (which is,

in effect, also stopped somehow)

- The current volume: A value between 0..127

- Our current sample rate (no idea if someone is interested but anyway, let’s

collect it)

- Current title, artist and album (if available)

So a simple struct to hold that state should look something like this:

/** the full exposed audio state in a struct */

#define AUDIOSTATE_STRLEN 100

typedef struct BTAudioState_ {

esp_a2d_connection_state_t connectionState; // 0=disconnected, 1=connecting, 2=connected, 3=disconnecting

esp_a2d_audio_state_t playState; //0=suspended, 1=stopped, 2=playing

uint8_t volume; //0..127

int sampleRate;

char title[AUDIOSTATE_STRLEN];

char artist[AUDIOSTATE_STRLEN];

char album[AUDIOSTATE_STRLEN];

} BTAudioState;

So what do we do now? Look into the logs (remember make monitor) for the data

we’re interested in. Find the code that generated the log messsage. Insert

code to update our state. Be sure to lock each access to the struct. After a

change, push an entry to the event queue. It’s a good idea to clear the state

when we get disconnected.

For example, we insert four lines to handle ESP_A2D_AUDIO_STATE_EVT,

an event sent whenever the actual stream is started, stopped or suspended:

case ESP_A2D_AUDIO_STATE_EVT: {

a2d = (esp_a2d_cb_param_t *)(p_param);

ESP_LOGI(BT_AV_TAG, "A2DP audio state: %s", s_a2d_audio_state_str[a2d->audio_stat.state]);

s_audio_state = a2d->audio_stat.state;

if (ESP_A2D_AUDIO_STATE_STARTED == a2d->audio_stat.state) {

s_pkt_cnt = 0;

}

lockAudioState();

audioState.playState = a2d->audio_stat.state;

unlockAudioState();

notifyAudioStateChange();

break;

}

There are other parts where the state is updated, but they all follow the same

principle, so it would be boring to list them all here. Try yourself! Or have a

look at the repo. lockAudioState()acquires the lock,

unlockAudioState() releases it and notifyAudioStateChang() pushes

an event to our queue.

Tapping the audio stream

bt_app_core.c has two tasks: The bt_app_task that responds to

bluetooth stuff and the bt_i2s_task that seems to stream the audio data

to the I2S peripheral. Bingo! That’s ideal!

Have a look at bt_i2s_task_handler: This function mainly consists of an

endless loop waiting on a ring buffer to deliver sample data and pushes

that data into the i2s peripheral. We can hack that! First, we want to

implement volume control by scaling each sample. Second, we want to calculate

the audio volume. Have a look:

static void bt_i2s_task_handler(void *arg) {

uint8_t *data = NULL;

size_t item_size = 0;

size_t bytes_written = 0;

static float leftSquares = 0;

static float rightSquares = 0;

static int sampleCount = 0;

for (;;) {

/* receive data from ringbuffer and write it to I2S DMA transmit buffer */

data = (uint8_t *)xRingbufferReceive(s_ringbuf_i2s, &item_size, (portTickType)portMAX_DELAY);

if (item_size != 0){

int16_t *buf = (int16_t*)data;

int numSamples = item_size / 2;

uint8_t vol = getVolume();

float volScale = volumeScale[vol] / 65536.0f;

// Sample processing can go here. Right now, only volume scaling and RMS analysis

for (int i=0; i<numSamples; i += 2) {

float l = (float)buf[i];

l *= volScale;

leftSquares += l*l;

buf[i] = l;

float r = (float)buf[i+1];

r *= volScale;

rightSquares += r*r;

buf[i+1] = r;

}

sampleCount += numSamples;

i2s_write(0, data, item_size, &bytes_written, portMAX_DELAY);

vRingbufferReturnItem(s_ringbuf_i2s, (void *)data);

if (sampleCount >= 1500) {

notifyAudioRMS(sqrtf(leftSquares / sampleCount), sqrtf(rightSquares / sampleCount));

leftSquares = 0;

rightSquares = 0;

sampleCount = 0;

}

}

}

}

This code is by no means elegant nor efficient. First, we cast the data buffer

to an int16 array (we know that we have 16 bit samples and I2S has them

typically interleaved, L/R/L/R/…). For each buffer, we request the current

audio volume, get a scaling factor via a lookup table (perceived volume is

logarithmic). Then we go through all left and right samples, convert each to

float and multiply it with our volume factor. Then we convert the sample back

to int and replace the sample in the buffer with our scaled value.

We also square each sample and sum the squares for the left and right channel.

After 1500 samples (roughly every 30ms for 44KHz), we divide the the sum of

squares by the number of samples, resulting in the mean square, and then take

the square root, resulting in the Root of the Mean Square (RMS).

That’s a good basis for a volume display. notifyAudioRMS() will push an

audio RMS update to the event queue. After reporting, we reset the accumulators

for the next interval.

Converting everything to float and back is terribly unneccessary and terribly

slow. But the ESP is fast enough and this is a good starting point for further

DSP (anyone?).

Bring it together

Now that we have extended the bluetooth audio code to give us callbacks

whenever something happens, it’s time to bring it all to the main loop. Let’s

see what we should do in the main loop:

- Audio state changed: Pull audio state, redraw screen

- Audio RMS levels changed: Remember levels, redraw just the level meter

- Home button pressed: Exit to launcher

- Joystick up or down: Increase or decrease volume, redraw all

First, write typedefs and structs that can hold audio events (state changes or

RMS updates):

typedef enum BTAudioEventType_ {

Event_StateChanged = 1, ///< audio state has changed, may be queried using getAudioState

Event_RMSUpdate ///< audio RMS update

} BTAudioEventType;

typedef struct BTAudioEvent_ {

BTAudioEventType type;

union {

struct {

float left;

float right;

} rms;

} data;

} BTAudioEvent;

Next generate a queue to hold these events:

audioQueue = xQueueCreate( 10, sizeof(BTAudioEvent) );

Now we need callback functions to call from the bluetooth part (running in

the the bluetooth task!). Their purpose is to push a BTAudioEvent into the

audioQueue:

/** callback from bt_app_av: state has changed */

void audioStateChange() {

BTAudioEvent evt = {

.type = Event_StateChanged

};

xQueueSend(audioQueue, &evt, 0); //evt is copied to queue

}

/** callback from bt_app_core: new volume measurement */

void audioRMSUpdate(float left, float right) {

BTAudioEvent evt;

evt.type = Event_RMSUpdate;

evt.data.rms.left = left;

evt.data.rms.right = right;

xQueueSend(audioQueue, &evt, 0); //evt is copied to queue

}

Next, register the callbacks (not shown: They will just be stored in global

variables and called when necessary)

setAudioStateChangeCB(&audioStateChange);

setAudioRmsCB(&audioRMSUpdate);

At this point, updates from the bluetooth stack will end up in our

audioQueue. Time to combine the queues:

QueueSetHandle_t queueSet = xQueueCreateSet(20);

xQueueAddToSet(buttonQueue, queueSet);

xQueueAddToSet(audioQueue, queueSet);

Finally, we can write our main event loop:

while (1) { //handle events from both button and audio queue

QueueSetMemberHandle_t queue = xQueueSelectFromSet(queueSet, portMAX_DELAY);

if (queue == buttonQueue) {

rp2040_input_message_t message;

xQueueReceive(buttonQueue, &message, 0);

if (message.state) {

switch(message.input) {

case RP2040_INPUT_BUTTON_HOME:

exit_to_launcher();

break;

case RP2040_INPUT_JOYSTICK_UP:

volume_set_by_local_host(audioState.volume < 122 ? (audioState.volume+5) : 127);

drawAll();

break;

case RP2040_INPUT_JOYSTICK_DOWN:

volume_set_by_local_host(audioState.volume > 5 ? (audioState.volume-5) : 0);

drawAll();

break;

}

}

} else if (queue == audioQueue) { //audio event

BTAudioEvent evt;

xQueueReceive(audioQueue, &evt, 0);

if (evt.type == Event_StateChanged) { //state changed: update main UI

getAudioState(&audioState);

drawAll();

} else if (evt.type == Event_RMSUpdate) { //RMS: Update bars

float leftDB = 20 * log10(evt.data.rms.left);

float rightDB = 20 * log10(evt.data.rms.right);

leftDBMeter = (leftDB - DBMETER_MIN) / (DBMETER_MAX - DBMETER_MIN);

rightDBMeter = (rightDB - DBMETER_MIN) / (DBMETER_MAX - DBMETER_MIN);

drawDBMeter();

}

}

}

The xQueueSelectFromSet will wait until am event arrives in one of the

queues and return which queue was active. The rest is dispatch: If the origin

was the button queue, react to button or joystick input. If it was an audio

event, redraw the level meter or the whole screen. The RMS update will convert

the RMS to dB by calculating the logarithm (as said above, perceived volume is

logarithmic). Then, the values will be scaled to fill the screen. The values

DBMETER_MIN and DBMETER_MAX are arbitrarily chosen so that the

level meter shows something useful.

Show it!

We’ve put some effort into collecting and merging data to display. Now it’s

time to visualize the data. The Badge comes with a convenient graphics

package that allows us to draw shapes and write text. It

draws to a bitmap and then transfers the bitmap to the screen. Currently, the

transfer to screen is not very fast as it uses the MCU to control the transfer

(anyone interested in implementing DMA transfers? Pull Request, plz!). Smooth

fullscreen animations will be difficult. However, it’s possible to just

transfer parts of the buffer. The only smooth animation we need is the level

meter.

For simplicity, let’s draw that as a horizontal bar graph (expanding to the

left and right from center for the left and right channel) at the bottom of the

screen and put it in a separate drawing function, drawDBMeter(). The

remaining screen is drawn in drawAll(), which will, in turn, call

drawDBMeter(). This way we can either update the DB graph quickly or the

whole screen slowly. Both functions will transfer their parts to the screen.

void drawDBMeter() {

if ((audioState.connectionState != ESP_A2D_CONNECTION_STATE_CONNECTED) || (audioState.playState != ESP_A2D_AUDIO_STATE_STARTED)) {

leftDBMeter = 0;

rightDBMeter = 0;

}

int halfWidth = (ILI9341_WIDTH / 2);

float l = (leftDBMeter < 0) ? 0 : (leftDBMeter > 1) ? 1 : leftDBMeter;

float r = (rightDBMeter < 0) ? 0 : (rightDBMeter > 1) ? 1 : rightDBMeter;

int leftPix = halfWidth * l;

int rightPix = halfWidth * r;

int p1 = halfWidth - leftPix;

int p2 = halfWidth + rightPix;

int y = ILI9341_HEIGHT-DBMETER_HEIGHT;

pax_col_t bgCol = pax_col_rgb(0,0,0);

pax_col_t fgCol = pax_col_rgb(255,255,255);

pax_simple_rect(&screenBuf, bgCol, 0, y, p1, DBMETER_HEIGHT);

pax_simple_rect(&screenBuf, fgCol, p1, y, p2-p1, DBMETER_HEIGHT);

pax_simple_rect(&screenBuf, bgCol, p2, y, ILI9341_WIDTH-p2, DBMETER_HEIGHT);

int off = 2 * ILI9341_WIDTH * (ILI9341_HEIGHT-DBMETER_HEIGHT);

ili9341_write_partial_direct(get_ili9341(), screenBuf.buf+off, 0, ILI9341_HEIGHT-DBMETER_HEIGHT, ILI9341_WIDTH, DBMETER_HEIGHT);

}

The code relies on the audioState struct and the leftDBMeter and rightDBMeter variables

(all are local to the main task, so we don’t need to worry about threading

here). DBMETER_HEIGHT is a global variable determining the height of the

bar in pixels and ILI9341_WIDTH and ILI9341_HEIGHT are variables

defined in the display driver component included with the template app. Drawing

is pretty straightforward:

- If we’re currently not playing music, the meter should be at zero

- Levels are clamped and then scaled to screen size

- The bar graph always consists of a white rectangle in the middle and two

black rectangles at the sides. It would be slightly easier to fill the whole

area black and then a white rectangle over it, but that would touch some

pixels twice. The three-rectangles-approach only sets each pixel once.

- In the end, the

ili9341_write_partial_direct() call transfers the

screen portion of the bar graph to the screen.

The drawAll() function is longer but even easier:

void drawAll() {

static const char disconnected[] = "Disconnected";

static const char connecting[] = "Connecting...";

static const char disconnecting[] = "Disconnecting...";

static const char stopped[] = "Stopped";

static const char playing[] = "Playing";

pax_col_t bgCol = pax_col_rgb(0,0,0);

pax_background(&screenBuf, bgCol);

pax_col_t fontColor = pax_col_rgb(255,255,255);

const char *status = "?";

switch (audioState.connectionState) {

case ESP_A2D_CONNECTION_STATE_CONNECTING:

status = connecting;

break;

case ESP_A2D_CONNECTION_STATE_DISCONNECTING:

status = disconnecting;

break;

case ESP_A2D_CONNECTION_STATE_DISCONNECTED:

status = disconnected;

break;

case ESP_A2D_CONNECTION_STATE_CONNECTED:

status = (audioState.playState == ESP_A2D_AUDIO_STATE_STARTED) ? playing : stopped;

}

char volStr[30];

snprintf(volStr, 30, "Volume: %i%%",audioState.volume * 100 / 127);

pax_draw_text(&screenBuf, fontColor, pax_font_saira_condensed, pax_font_saira_condensed->default_size, 10, 10, status);

pax_draw_text(&screenBuf, fontColor, pax_font_saira_regular, pax_font_saira_regular->default_size, 10, 90, audioState.title);

pax_draw_text(&screenBuf, fontColor, pax_font_saira_regular, pax_font_saira_regular->default_size, 10, 115, audioState.artist);

pax_draw_text(&screenBuf, fontColor, pax_font_saira_regular, pax_font_saira_regular->default_size, 10, 140, audioState.album);

pax_draw_text(&screenBuf, fontColor, pax_font_saira_regular, pax_font_saira_regular->default_size, 10, 165, volStr);

ili9341_write_partial_direct(get_ili9341(), screenBuf.buf, 0, 0, ILI9341_WIDTH, ILI9341_HEIGHT-DBMETER_HEIGHT);

drawDBMeter();

}

The function just clears the screen and then writes some text to it. Most of

the code just determines the message to draw.

ili9341_write_partial_direct() transfers everything except for the volume

meter and calls drawDBMeter() to update that part.

This should be it. Make and install again (and, if needed, debug, rinse,

repeat). There should be awesome sound and an awesome user interface.

Publishing

The Badge.team hatchery also allows publishing native apps. Go to The Hatchery,

register, login. There should be an option to publish native ESP32 apps. This

tutorial is already way to long, though. Follow these instructions if you want

to publish your app in The Hatchery

3 - ESP-IDF fancy name tag

There are endless games and apps to explore on the badge, but when going about your business on the camp, most likely its main function will be a name tag. So what better than writing a custom name tag to show off your style, identity, hacker skills, memes, or whatever you want.

After having completed the getting started you should have a template app that can draw a colored background and some text. Change the text to your name, and you have yourself a name tag… right? Let’s explore some ways in which you can spice up your name tag.

Other drawing functions

The pax-graphics documentation has quite a nice list of all the fonts and drawing primitives it contains.

Drawing lines and circles may sound a bit boring, but if you duck “line patterns” or “geometric pattern” or similar queries you can find quite some nice patterns to draw with those basic shapes.

In addition I’d like to draw your attention to the shaders documentation which has a nice example to draw rainbows on shapes, which you could easily adapt to do all sorts of nice gradients.

Drawing images

Geomeric patterns are nice, but if you want to show off your art, the logo of your favourite retrocomputer, a character from your favourite franchise, or your favourite meme, you’ll want to load images onto the screen.

The pax-graphics side of drawing images is well documented. But before you get to that point, there are a few things you need to do.

Of course first you need to find or make an image. This part is up to you. Keep in mind that the badge screen is 320x240 pixels, and that pax-graphics only loads png.

Next you’ll need to get the image onto the badge. Since internal flash space is extremely limited, it’s highly recommended to use a micro SD card. Be careful when inserting it! To push the png image to the SD card:

python3 tools/webusb_fat_push.py myimg.png /sdcard/myimg.png

To use the SD card, you need to include the component, and mount it. Then you can open the file.

#include "sdcard.h"

// image buffer

static pax_buf_t myimage;

// mount sd card

esp_err_t res = mount_sd(GPIO_SD_CMD, GPIO_SD_CLK, GPIO_SD_D0, GPIO_SD_PWR, "/sd", false, 5);

if(res != ESP_OK) ESP_LOGE(TAG, "could not mount SD card");

// open file

FILE* fd = fopen("/sd/myimg.png", "rb");

if(fd == NULL) ESP_LOGE(TAG, "could not open file");

// store as a buffer for later use, best for animations

if(!pax_decode_png_fd(&myimage, fd, PAX_BUF_16_565RGB, 0)) ESP_LOGE(TAG, "could not parse png");

pax_draw_image(&buf, &myimage, x, y);

// or draw directly, simplest for static drawings

if(!pax_insert_png_fd(&buf, fd, x, y, 0)) ESP_LOGE(TAG, "could not parse png");

If you do not have a micro SD card, and you only want to load a small image, you can also mount the internal filesystem instead.

Making animations

An animation is just some static drawings in a row. Once again, it’s what you do with it.

The template app already has an infinite loop that waits forever until a button is pressed. Do not remove that part! The ESP32 is running an RTOS that needs to do some book keeping in the background. Without some delay somewhere you’ll get watchdog timer errors. However, you can change the line to the following, to only wait a few milliseconds instead of forever. Tweak this number to get the frame rate you want, or to make a nice slideshow.

xQueueReceive(butonQueue, &message, pdMS_TO_TICKS(1));

If you can’t get the framerate you want, and are doing a lot of rendering in pax-graphics, you can offload that to the second core for a free speed boost.

If that still isn’t fast enough, you should hop over to the FPGA section, which has a faster parallel bus to the display.

As for what kind of animations to make, a great source of inspiration is demoscene videos. Here is a page that has some implementations of a few of the classic effects, but there are plenty of other cool effects to be found all over the internet. Who’s going to implement Nyan Cat, Bad Apple, old Windows screensavers, and more?

RGB galore

The badge includes a kite of RGB LEDs, which you can do cool blinkenlights with. The API is pretty simple: First you need to enable the power gate to the LEDs, then you init it with the correct output pin, and then you send an array of PWM values.

#include "ws2812.h"

// enable power to the LEDs

gpio_set_direction(GPIO_SD_PWR, GPIO_MODE_OUTPUT);

gpio_set_level(GPIO_SD_PWR, 1);

// initialise them

ws2812_init(GPIO_LED_DATA);

// send data

uint8_t led_red[15] = {0, 0xFF, 0, 0, 0xFF, 0, 0, 0xFF, 0, 0, 0xFF, 0, 0, 0xFF, 0};

ws2812_send_data(led_red, sizeof(led_red));

As an example, here is the kite animation that plays when you start the badge.

Making sound

TODO: There isn’t a nice API for this yet. You can steal some code from the launcher maybe.

Using sensors

TODO: Make some nice example with the BNO055 component